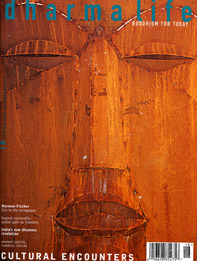

The Roshi and the Rabbi

Norman Fischer, a leading Zen teacher, explains to Vishvapani his initiatives to revive Jewish spirituality through meditation

Dharma Life: You are a leading figure in American Zen, but you are also active in the Jewish community. Why did you turn away from Judaism and become a Buddhist in the first place?

Norman Fischer: I had a Jewish upbringing. We went to synagogue and I became good at saying the prayers and so on. One rabbi was very influential in my life and I was close to him. I had a positive feeling about being Jewish, and I still am happy and proud that I had that heritage. I don't feel I rejected or ran away from it. I recognise problems with it, but it's like the family. You think, 'These are the family problems. That's OK.'

But the philosophical or religious questioning that led me to Buddhism just didn't seem to be the same kind of thing as Judaism. I saw that as a way of life, and I didn't see around me people who were striving to understand life. I saw people who were just doing what you are supposed to do, 'This is what you do when you are Jewish. You eat like this and so on.' It never occurred to me to consider Judaism as a path that could answer the questions that concerned me. So I was looking for something that had nothing to do with Judaism.

The presentations of Zen that I read by DT Suzuki and others didn't describe Zen as an alternative to other religions in the way I understood the term. They talked about Zen as a way of practice that is free of any religious point of view or perspective, and they depicted Zen meditation as a universal access to the spiritual way. So rather than feeling I was going outside my tradition, I felt I was finding something that wasn't available in that tradition.

DL: How did your renewed interest in Judaism come about?

NF: My mother died. It wasn't that I had a sudden upsurge of Jewish sentiments, but I wanted, in grieving for my mother, to say the kaddish for her - that would have meant something to her. So I went to the local synagogue, and felt a little strange turning up there. Fortunately there was an understanding Rabbi; I explained my situation, and he said, 'Sure. I respect what you have been doing, and I honour the effort you've made.' I had expected to be seen as a pariah for having taken up another religion.

I went to the synagogue regularly for 11 months and found to my surprise that I enjoyed it. It was a beautiful practice, and I felt very connected with my parents. I'd lived far away from them, and had not had much contact. Nor had I done the meditation practice which I think is necessary for all western Buddhists - that is, developing through meditation loving kindness and gratitude to our parents for what they have given us. So Jewish practice gave me a way of coming closer to my parents, and that was important for me. After all, Judaism has always been more of a family tradition rather than an individual quest.

I have a close friend, Alan Lew, who was a Zen student with me for a year, and later became a Rabbi. He eventually returned to his own meditation practice and became passionate about creating a Jewish path of meditation practice. As I was beginning to enjoy and participate in Jewish religion, Alan moved back to San Francisco. We began doing Jewish meditation retreats, and in that way I have been getting more involved. That involvement has been wrapped up with my friendship with Alan.

DL: Tell me about your work in teaching meditation in Jewish contexts.

NF: Since retiring from the Zen Center recently I have set up a foundation for sharing Zen teachings in a variety of settings with the world at large. We need strong traditions, but we also need some like me who reach the people who inhabit the gaps between traditions. We have serious problems in the world, and we need a critical mass of clear-headed, compassionate people. So I am just freely entering the world in a variety of ways, and one way is as a Jewish meditation teacher.

Rabbi Lew and I have been working on this for many years and we now have a center devoted to this work. It has made me study the Bible, and I've written a book with my own versions of the Psalms. So this has got me into Jewish material, which has been fascinating. I realise how little I ever knew about Judaism.

I knew my family situation and the things we did, but actually, like most Jews, I was quite ignorant about Judaism. I am having fun studying Judaism with a view to understanding it through the eyes of meditation practice, and trying to create a way of looking at the Jewish tradition based on meditation. Judaism needs renewal. There are many renewal movements and the meditation aspect of renewal is an important one.

DL: But can you really combine Judaism and Buddhism?

NF: We are not trying to do that. What we are doing is practising meditation, on the theory that meditation practice in and of itself isn't limited to Buddhism; it is a universal unfolding of the human heart. We are trying to use meditation practice to awaken Jewish people to the spiritual riches within Judaism. So it isn't Buddhism.

DL: None the less you personally are practising two religions. What about issues such as believing in God?

NF: It depends what you mean by God. Rabbi Lew tells a story: someone comes to him, very angry, and says, 'I'm mad because I don't believe in God!' So the Rabbi says, 'Describe for me the God you don't believe in'. So the person does that, and Rabbi Lew says, 'Well, I don't believe in that God either.'

God to me is the word to describe the sense of presence that is larger than any individual or individual entity. So if God is a Supreme Being then, no, I don't think there is a Supreme Being. But there have been many volumes of theology written on God and very few of them depict God as a Supreme Being. You have to pick carefully through them philosophically to see where they differ from Buddhist thought.

To me the truth exists irrespective of its various descriptions, whether one has a feeling for it or not. So I feel no conflict of belief. I understand that there is an approach to Buddhism that defines Buddhism as 'this', and the same with Judaism. And if you are a Jewish or a Buddhist person you believe these things or feel these ways. We tend to say that Judaism is this, and Buddhism is that. But you don't have to look at it that way; you can have your own experience and sensibility about things. My approach to Zen is rather to say - here is an open way of exploring life.

DL: Buddhism is about letting go of a fixed sense of identity. But Judaism, and even Jewishness, are very much about belonging, about identifying with a culture and a race. What does that have to offer someone who is in the process of letting go? What is the value of returning to Jewish roots?

NF: I don't know that there is a value, and I don't go around saying, 'You should be returning to your Jewish roots!' But my observation is that some people with Jewish heritage for some reason - I guess I would ascribe it to karma - are in connection with that Jewish identity. Either they are in reaction to it, or they are confused; maybe they are going towards it, or embracing it. There are other people who are just as Jewish in their background for whom it doesn't seem to matter. I don't think they are avoiding anything, and I wouldn't tell them to go look at their Jewishness.

We all have identity. There is no being a person without an identity. If you are trapped in your identity, whether that is 'being a Jewish person' or 'not being a Jewish person' then either way you are suffering. But it is possible to embrace being Jewish as the identity to which you are karmically wedded, without being myopic and limited. For it's not the alpha and omega of what you are - ultimately you are Buddha Nature.

DL: What does it mean to be Jewish in the modern world, in any case?

NF: I can't say. Hitler really did his work. He was the last nail in the coffin of Judaism as it has been known for all these years. That's sad. In America Jews are confused. There are still some who are able to be comfortable as European Jews, but in a couple of generations there won't be any of them left. Israel is in a hopeless political and spiritual mess, and in an untenable position. So Judaism needs to be reinvented and reconstituted, and if Judaism survives it will be different. Meditation practice can really help with that.

DL: It does seem odd and surprising that Zen can help in Jewish revival. What can Zen offer?

NF: Judaism developed a powerful spirituality that depends on cultural know-how. That started to end with the European enlightenment, and the process of secularisation weakened Jewish spirituality. So much depends on knowing Hebrew, and with the loss of knowledge of the language Jewish spirituality becomes less available. People can't reproduce the experience of previous generations.

But Buddhist meditation is available. It's not unusual for a religion that has run out of steam to adapt ideas from another tradition: in the past Judaism was revived through its contact with Islam and Greek thought. Cultures have never been isolated, and it really isn't a problem to introduce meditation within Judaism. Purists may object, but for Judaism not to offer access to its own spirituality is a mistake.

I realise this is tricky and one could become a spiritual supermarket vendor, but you also have to be careful of becoming myopic. There is a tool in Buddhism that can be used in other traditions. Other traditions seem to be proposing a metaphysical truth with all the trappings, whereas Buddhism teaches that there is no underlying metaphysical truth. So Buddhism has a wonderful role to play because, at its heart, it isn't actually 'Buddhism' in any case. That's why you can have a new development like the Western Buddhist Order, trying to create western Buddhism, because Buddhism cannot be fixed.

DL: You say that Judaism is obsessed with language and approaches meditation through language. In Zen we think of meditation as something beyond words. How do you work that? And is there something in the tension between the two that informs the way you write?

NF: Definitely. Language is our prison and also the way out of the prison. All my poetry concerns a fundamental doubt about language and expression. But all religious language is about that. In Judaism there is a huge emphasis on the scriptures, but the subject matter is how to go beyond that - because whenever you are talking about God you are talking about that which is beyond anything we can define or articulate. But you use language to reach that point.

To be human is to be in that point of tension. If you have no spiritual sensibility you may be totally caught up in language without recognising that you are not language. But as soon as you become a religious person or a meditator, or find some point of entry into silence, you realise you can never escape from language; and you see that the human struggle is to find the unsayable within the sayable.

In translating the Psalms, I've become interested in the issue of the name of God. That is the ultimate word, right? But the name of God is an unknown, unpronounceable word. The letters written do not make a name, they stand for the name which is unnameable. So I render 'the name' as 'your nameless name'. Language is in a constant struggle with the unsayable. I think our human dilemma is how, in this form, which is always concrete and particular, we can enter that which is beyond this form. Judaism does it through emphasising language, which has its limitations. Zen does it with reference to silence, which also has limitations.

DL: In your book Jerusalem Moonlight you also speak of your attraction to Judaism's awareness of darkness. What does this mean?

NF: Rabbi Lew says, 'Buddhism makes sense. That's its strength and its weakness'. You can't be a clergyman without disagreeing with some aspects of Buddhism. But in a way Buddhism is too nice, too good. We need some aspects of the other side of life. I am a poet, and the dark is partly what interests me. The Jewish scriptures are a record of a deeply symbolic struggle in the human heart.

God may not differ essentially from Buddha Nature, but one great difference is that God is a 'character'. God can be argued with, and that allows space for the human need to yell and complain. That's language. It gives opportunity to the raging mind, and for an ongoing dialogue with the cosmos. That's a perennial mode of being. Why do I need to say anything to God? Because I am human.

Opening to You:

Zen-inspired translations of the Psalms

By Norman Fischer

Putnam Penguin 2002; £13.95/$19.95

Psalm 90

You have always been a refuge to me

Before the mountains, before the earth,

before the world

From endlessness to endlessness

You are

You turn me around.

You say,

Return child

A thousand years to you are like a yesterday

Like a lonely hour in the middle of the night

You rush them away like a flood

Like a long sleep

Like grass

That rises up fresh in the morning

And in the evening withers

I am consumed by you

Terrified by time

And my despair is all too clear

In the light of your face

All my days pass

In the your midst

All my years reverberate

Like a solemnly spoken word

The years of our life number seventy

If we are uncommonly strong maybe eighty

Yet they only bring trouble and sorrow

For we can't forget how soon they pass

How swiftly they fly by

Who knows your power?

I can only fear it in the darkness of every night

Help me understand how to count my days

How to embrace my life

That I may nourish a heart of wisdom

Turning around: how long, O Lord, how long!

Think of me

Satisfy me in the morning with your kindness

And I will rejoice all day long

Give me as many days of joy in you

As the days of my natural suffering

The days of my longing and my sorrow

Show me how

You live in me

Bless my children

Light my path with your beauty

So that all that I do will be inspired

Yes, establish my life in you

And let all that I do

Be yours